In this world we try to construct our being out of our doing – that’s the type of world we live in. This is the type of message we have been given right from the word ‘go’. We are encouraged to ‘do’, we are (to some extent or another) given support for our ‘doing’; we are on the other hand given zero encouragement to ‘be’, we are given zero support for our ‘being’. We’re actively penalized for ‘being’, since to be is to drop out of the social game that we are all playing, and ‘dropping out of the game’ has never been encouraged by any society.

‘Doing’ is very highly valued in the Western world – the implication is always that it will lead to something great, the implication is always that it will definitely need to some marvellous state of being. This is precisely where our error lies, therefore. Successful doing can of course lead to a highly desirable socially-constructed identity (just as being unsuccessful can lead to another, rather ‘less desirable’ type of socially–constructed identity), but ‘identity’ is not at all the same thing as being. It is a substitute for it, but it is not the same thing.

There is no being in identity! This is the same as saying that there is no being in a label, or no being in a mask – of course there isn’t! What could be hollower than a label or a mask? To chase after an identity as if this were the same thing as being is therefore the road to nowhere. No matter what sort of identity we obtain as a result of our efforts it’s not going to do it any good – all identities are the same, all identities are hollow. It doesn’t make any difference whether it’s a socially-approved identity or a socially-disapproved one, it doesn’t matter whether it’s a highly prized ‘winner identity’, or a not-so-highly-valued ‘loser identity’ that we have obtained for ourselves – it is hollow either way.

We never really look at this idea, the idea that says it is possible to be someone as a result of ‘successful doing’ (which is the idea that the idea that we can somehow find being through our doing). The pain caused by our lack of being drives us unrelentingly; it causes us to put that special emphasis on our goal-orientated activity. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with goals therefore, only that if the goal we are chasing secretly stands for our ‘missing being’ then the effort we are putting into this endeavour is always going to be wasted effort’. We are busy chasing an illusion in this case. Whenever we get too serious, too driven in relation to our goals this is because we are – unbeknownst to ourselves – trying to obtain ‘being’ as a result of our ‘successful doing’. Whenever we get humourlessly fixated in this way, then it is inevitably the case that we are actually trying to find our ‘missing being’. We are looking for it in a place there it isn’t, in a place where it never can be. How can our ‘missing being’ be tied up with the realisation of some concrete goal? Or to put this another way, how could we ever make a goal of finding our ‘missing being’ when we don’t have the faintest clue as to what this missing being is, or what on earth it would look like even if we did find it? How is this endeavour ever going to work out for us?

We don’t of course know that we are trying to find our missing being as a result of our tightly-focussed goal-orientated behaviour. If we knew that then we would be on the right track! We don’t know this at all – we don’t have the faintest clue as to what our real motivation is, we don’t actually have any reason to suspect that it isn’t what it declares itself to be. Our situation – therefore – is that we unconsciously believe that we can make up for our inner, invisible deficit (the deficit that comes with identifying with the mind-created image of ourselves) by engaging in the correct type of goal-orientated behaviour; a more conventional way of expressing this would be would simply be to say that we believe that we can ‘fundamentally or radically better ourselves’ on purpose, by pure effort of will.

In one sense (admittedly a very superficial sense) this assumption is true – by exercising and taking care of our physical body and eating well and adopting what is generally called a ‘healthy lifestyle’ we can indeed ‘improve our situation’; in terms of what really matters in life however – which is (we might say) ‘to reconnect with who we really are’ (or ‘re-engage with the authentic inner life that we have long-since forgotten about’) there are no logical/purposeful steps that we can take to bring this about. No one can make a goal of remedying their inner deficit (or rather we can do but not in a meaningful way) – no matter what goal it is we come up with, it’s never going to be more than an extension (or projection) of our own unconsciousness. Who we really are can’t be made into a ‘goal’ and so there can be no such thing as ‘the right type of goal-orientated behaviour that can somehow bring it into being’.

Goals are doing (just as theories and strategies and the actions that arise out of these theories are ‘doing’) and being can never come about as a result of doing! Not even the most determined, assiduous, high-intensity doing that there ever was can bring about actual being – if there isn’t any actual being at the beginning of things then there can’t be any at the end. Unreality can’t be turned into reality no matter how hard we labour at it! It is actually a deficit in being that drives all our overvalued purposeful activities – if we felt complete or full on the inside then of course we aren’t going to be ‘overly goal-orientated’. We would no longer be so very hungry, so very needy… As the mystics have been saying for thousands of years, it is the ‘unconscious or unacknowledged perception of a lack of completeness’ causes us to crave completeness without knowing what it is that we are craving. and it is this ‘craving’ that accounts for most of the everyday activity we see around us. This type of ‘displacement-motivation’ is what drives the economy – we’re looking for ourselves in the wrong place!

So within the mystical/spiritual traditions it might be said that we are ‘grasping at illusions’ and that it is this misguided activity that brings us so much unhappiness. This – quite possibly – may not make very much sense to us – we may object for example that that what we are busy grasping at are real things, not illusions! Who is attracted to illusions. after all? The point is however that we are not so much grasping for the things themselves but what they represent to us without us even realising that they are representing anything! The things we are grasping at, are trying to obtain, hold an extra degree of attractiveness to us because they seem to be promising us some special, magical ‘X factor’ that we can’t help being magnetically attracted to. We’re attracted but we don’t ever wonder why we’re so attracted. We just know that the object of our desire is promising us ‘something great’ and that is good enough for us! We know on some level or other that there’s ‘something good out there in the world’, something good that we don’t have, and so we are very keen indeed to get our share of the special thing (or magical quality) that we feel we are missing out on! Everyone wants a slice of the pie after all, and that’s what consumerism is all about.

This is why ‘doing’ is idolised to the extent that it is in our world therefore. Nothing inspires us as much as ‘the myth of the supremely successful doer’ and all we can do is to try to approximate that myth as best we can in our own lives. All we can do is try to get some of that special action kudos to work for us! We’re too fast off the starting block though – we’re too fast off the starting block because we’ve got things the wrong way around – we don’t produce being out of doing, but rather being produces doing.

We have put the cart before the horse and things just aren’t going to work this way! There is a parallel to this idea in Taoism and the philosophy of Eastern martial arts where it is said that action is only effective when it comes out of stillness. Very much along similar lines, D. H. Lawrence writes: “One’s action ought to come out of an achieved stillness: not to be a mere rushing on.” Stillness is where our good sense lies (our wisdom rather than our intellectual smartness) and if our actions don’t come out of stillness they’re not just going to be ‘ineffective’, they’re going to be painfully counter-productive (or self-defeating).

This is actually a pretty fair assessment of what’s going on in the world around us, the world of human affairs – lots and lots of doing that hasn’t come out of ‘stillness’ (or ‘wisdom’) at all! Our doing has become extraordinarily ‘clever’ (‘clever’ in a superficial sense, that is) and this of course makes things worse for us not better. Mankind has been self-defined as ‘the tool-using animal’ and our tools are becoming ever more sophisticated – they are in fact becoming ever more sophisticated at an exponentially-increasing rate. And the result of this is that we are now living in a world that has been created as the result of the invisible assumptions that lie behind our tools being played out (or concretized) in the form of the concrete environment within which we live. It is as if our tools bring with them unwanted side-effects that define us and our world without us even being able to see how we have been defined. We didn’t see the ‘side-effects’ coming, and we don’t see them when they arrive either – we don’t see them when they arrive because it is the ‘side-effects’ of our tool-use (which is to say, the conditioning effect of the invisible limitations inherent in our assumptions) that determine precisely what we see and cannot see.

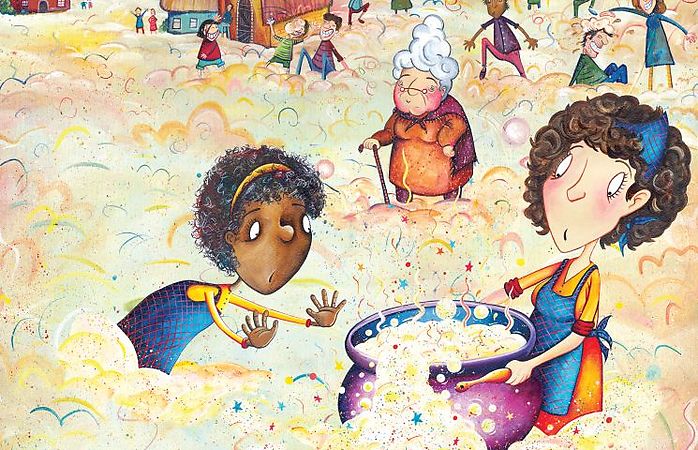

Enacting the age-old principle therefore, ‘the tool usurps the user of the tool’; the servant/instrument overthrows the master and no good is ever going to come about as a result of this. This very simple principle is illustrated by the fairy tale of the Magic Porridge Pot, which can feed the hungry if it is used properly, but which will drown the whole village under six feet of run-away porridge if there is no one there who actually knows how to use this valuable tool. ‘Knowing how to use the tool’ means knowing how to stop using the tool when the job is done, and if we don’t know how to do this (as we don’t) then disaster is only just around the corner. This motif is also echoed in such tales as Why the Sea is Salt (and ‘The Master and his Pupil’). A more modern variant of this theme is of course the well-known science fiction motif of ‘Frankenstein’s monster’, typified by the Terminator series of films (see for example, ‘The Rise of the Machines’). ‘Frankenstein’s monster’ is our own ‘disconnected cleverness’, which is directly analogous to what we have been calling ‘doing without being’.

On a personal/individual level, we might say that this comes down to ‘reacting’ rather than consciously responding (or not responding, as the case may be). It is perfectly possible – if not more-than-just-possible) to go through the whole of our lives ‘running on reflex’, reacting mechanically without ever questioning our own reactions. Without a shadow of a doubt, this ranks as the most ‘suffering-producing’ way of living that they ever could be – we ricochet from one painful situation to another in the most senseless way imaginable, and we call this ‘living our lives’. This is after all the only type of life we know; as far as we’re concerned there is no other type and all we can do is endure it as best we can. On the collective level, it may be said that we have ‘externalised our mechanical reflexes’ and turned them into an entire environment which we inhabit – a conditioned environment which defines our lives for us. This is of course no better than the first scenario we mentioned, which is where we allow our internal reflexes of thoughts or behaviour to run our lives for us, as if there is actually some sense inherent in them!

Ultimately, both the internal reflexes and the external ones (i.e.the ‘Machine Environment’) are one and the same thing, which is that thing that David Bohm calls ‘the system of thought‘. The remedy either way is simply for us to learn how to turn the machine/servant off, so that it doesn’t run our lives for us. The horse needs to be put before the cart again, if the natural order of things is to be restored. Instead of ‘doing–without–being’ (or ‘disconnected doing’), we need to bring being back into the picture again. This is of course easier said than done but it is a perfectly natural process that we are talking about here (rather than some sort of artificial imposition) and all we need to do in order to work with this natural process (instead of against it) is to see how we have got everything back to front, to see how we have put the cart before the horse. We can’t stop all of this heedless, runaway mechanical doing (all of this ‘disconnected cleverness’) on purpose (‘by force’, or by ‘will power’) but what we can do is allow ourselves to see that ‘being can never come from doing’, and when we can clearly see this we will inevitably stop putting all our money on a horse that can never win. We’ll still put some money on this horse of course – we will continue to invest in our automatic behaviour patterns to some extent – but ‘the heart will have gone out of it’, so to speak. We will no longer believe that we can create being with our frantic competitive doing and so we won’t be ‘lost in that doing’ in the completely immersive way that we were before. We will start to separate ourselves from our rational thinking and our purposeful doing and it is this process of separating ourselves from the illusion-seeking behaviour (which is sometimes called ‘the process of disidentification’) that brings about our actual being, or actual presence in our lives.